|

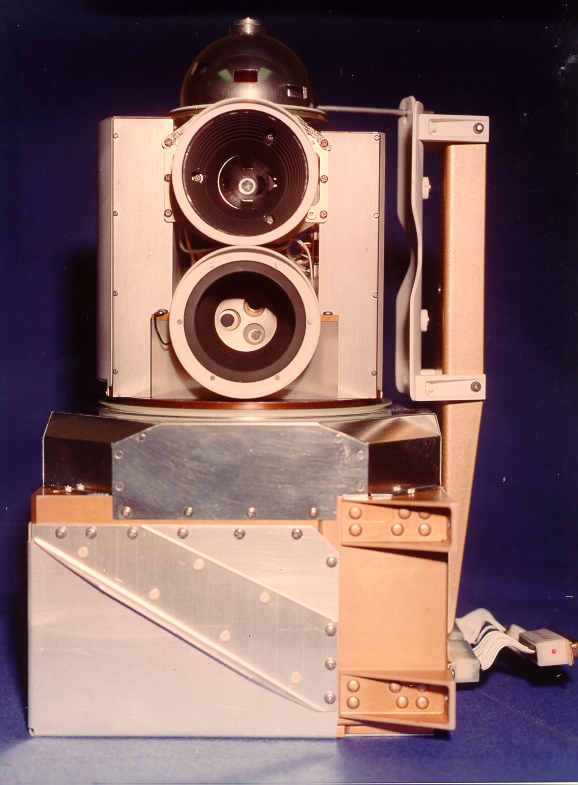

Fundamental TechnologiesVoyager LECP Pages |

by Sheela Shodhan

5.1 Calculations

The geometric factor G of a detector for a particular energy is the sum over all the sampling areas of the detector of the product of the sampling area of the detector and the solid angle spanned by the open trajectories that connect the sampling area and the open aperture, i.e.:

|

where n is total number of sampling areas on the detector,

DAi is the area of the ith. element on the detector,

DWi is the solid angle spanned by the open trajectories

� �j = 1npasDqj Dfj sin( qj+[(Dqj)/2])

Dq,Df are the intervals at which the polar and the azimuthal angles are scanned respectively and npas is the number of trajectories connecting DAi and the open aperture.

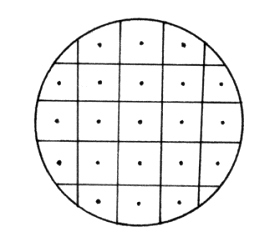

5.1.1 Determination of DAi

Each of the circular detector surfaces is divided into several sampling areas DAi. Each one of these circular surfaces is fitted into a square which is then further divided into smaller squares. The centres of each of these smaller squares which fall within the circular detectors have been considered as to sample that particular area element. Those squares that contain the centre point but are cut off by the circular boundary of the detector have been approximated as trapezoids.

Then starting from a particular center point on the detector, for a particular energy, the solid angle is determined.

Figure 5.1. The detector surface divided into several sampling areas. The dotted points are the initial points of the trajectory.

5.1.2 Determination of the solid angle

For a given energy, starting from a particular point on the detector and with a particular set of polar and azimuthal angles, the motion of this particle is observed inside the sensor subsystem. The coordinates of these points are included in Appendix D. The equations of motion:

dX/dt = V

M dV/dt = q/c V � B

are solved by Hamming's modified double precision Predictor-Corrector method in a "time reversed sense." "Time reversed sense" because the starting point on the detector surface in this calculation is the end-point of the real particle. At every stage of the trajectory calculation the fate of the particle is determined as discussed later. If this particle's trajectory passes through the open aperture of the sensor subsystem then it is considered as escaped. The polar and the azimuthal angles at the aperture are computed and npas is incremented by one. However, if the particle hits any of the surfaces of the sensor subsystem then it is considered lost and thus ignored since the real particle would also not be able to hit this point on the detector. Then a new set of polar and azimuthal angles is chosen and this process is repeated. Thus, polar and azimuthal are scanned at specific intervals to determine whether the particle escapes or not. A specific range of these for which the particles escape the sensor subsystem forms the set of trajectories that connect the sampling area and the open aperture. Then the solid angle spanned by this set of trajectories is computed using the above equation.

5.1.3 Determination of the fate of the particle

Given the line-segment formed by the points (xi,yi,zi) and (xi+1,yi+1,zi+1) of the trajectory to determine whether the particle is lost or not, the process is as follows:

For each of the steps above from (1) to (5) the relevant equations used are included in Appendix C.

In this way, the trajectory calculation continues until a decision is made as to whether the particle hits any of the surfaces and is lost or it passes through the opening aperture and escapes.

5.2 Discussion of the Results

Since at every stage in the particle's trajectory its curvature is determined by the local relation,

r = mcv/Bq (in c.g.s. units)

the deflection of the low energy electrons should be more than that of the high energy ones. This explains the fact that the Beta detector, which is closer to the opening aperture than Gamma, primarily collects low energy electrons while the Gamma detector collects higher energy electrons.

On examining the trajectories of the particles of different energies emanating either from the Beta detector or the Gamma detector, we do observe that the low energy electrons are indeed deflected more than the high energy ones. This also manifests itself in the shift of the azimuthal angles for which the particles escape, from lower angles to higher angles, as the energy increases. For example, for the energy E=480 keV the range of azimuthal angles for a point on the Gamma detector is 167 to 227 deg. while for the same point for energy E=720 keV the range has shifted to 181 to 228 deg.

Also, for a particular energy, due to the inhomogeneity of the magnetic field, the curvature of the trajectory of the particle depends upon its position in the deflection system. In this time reversed calculation, the particles entering the deflection system into the region where the field is higher have higher curvatures (less radii) whilst those particles that enter into the region of lower field have lower curvatures (high radii).

Together with this field inhomogeneity which shapes the trajectory of the particles, the surfaces of the sensor subsystem restrict the values of the angles for which the particles escape to a finite range instead of all the allowable values.

Besides, we also expect the symmetry about the z = 0.0 plane in the magnetic field and in the modelled sensor subsystem, to be reflected in the angular distributions of the escaping particles at the detectors and at the apertures.

The above observations support the validity and the correctness of the magnetic field model.

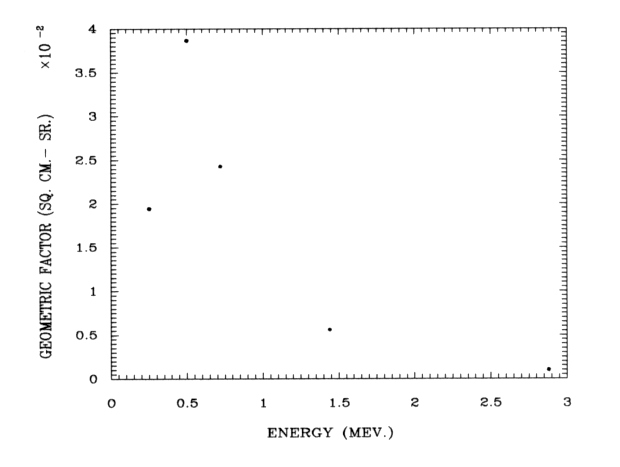

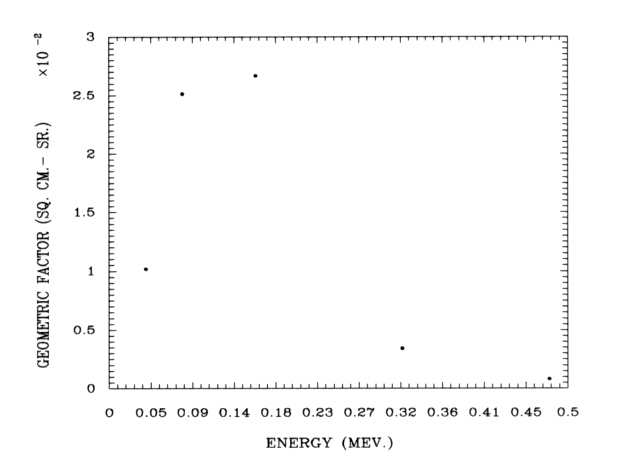

5.2.1 Variation of the geometric factors with energy

| DETECTOR | ENERGY keV |

GEOMETRIC FACTOR cm2 sr |

|---|---|---|

| Beta | 40 | 0.010177 |

| 80 | 0.025129 | |

| 160 | 0.026672 | |

| 320 | 0.003406 | |

| 480 | 0.000803 | |

| Gamma | 250 | 0.019426 |

| 500 | 0.038626 | |

| 720 | 0.024262 | |

| 1440 | 0.005594 | |

| 2880 | 0.000992 |

Table 5.1. Geometric factors for different energies for the Beta and the Gamma detectors

5.2.2 Tables of the number of particles that pass

Figure 5.2. Variation of the geometric factors with energy for the Gamma detector.

Figure 5.3. Variation of the geometric factors with energy for the Beta detector.

Figure 5.4. Points on the Gamma detector which are the initial points of the trajectories.

| 2 | 4 | 6 | 8 | 10 | |

| 2 | 499 | 526 | 499 | ||

| 4 | 498 | 528 | 531 | 528 | 498 |

| 6 | 528 | 557 | 576 | 557 | 528 |

| 8 | 552 | 576 | 576 | 576 | 552 |

| 10 | 568 | 564 | 568 |

Table 5.2. Number of particles that pass for different points on the Gamma detector for E=500 keV. Note: The scanning intervals Dq, Df = 2 deg.

| 2 | 4 | 6 | 8 | 10 | |

| 2 | 245 | 265 | 245 | ||

| 4 | 286 | 301 | 314 | 301 | 286 |

| 6 | 331 | 346 | 1402* | 346 | 331 |

| 8 | 361 | 387 | 379 | 387 | 361 |

| 10 | 419 | 404 | 419 |

Table 5.3. Number of particles that pass for different points on the Gamma detector for E=720 keV. Note: The scanning intervals Dq, Df = 1 deg for point marked by *, for all others, Dq,Df = 2 deg.

| 2 | 4 | 6 | 8 | 10 | |

| 2 | 32 | 37 | 32 | ||

| 4 | 31 | 54 | 64 | 54 | 31 |

| 6 | 60 | 83 | 350* | 83 | 60 |

| 8 | 93 | 106 | 114 | 106 | 93 |

| 10 | 125 | 137 | 125 |

Table 5.4. Number of particles that pass for different points on the Gamma detector for E=1440 keV. Note: The scanning intervals Dq, Df = 2 deg and for points marked *, Dq, Df = 2 deg.

| 2 | 4 | 6 | 8 | 10 | |

| 2 | 0 | 10 | 0 | ||

| 4 | 0 | 13 | 37 | 13 | 0 |

| 6 | 10 | 53 | 74 | 53 | 10 |

| 8 | 45 | 93 | 120 | 93 | 45 |

| 10 | 151 | 162 | 151 |

Table 5.5. Number of particles that pass for different points on the Gamma detector for E=2880 keV. Note: The scanning intervals Dq, Df = 1 deg.

Figure 5.5. Points on the Beta detector which are the initial points of the trajectories.

| 2 | 4 | 6 | 8 | 10 | |

| 2 | 124 | 140 | 124 | ||

| 4 | 54* | 67* | 70* | 67* | 54* |

| 6 | 107 | 129 | 142 | 129 | 107 |

| 8 | 97 | 123 | 66* | 123 | 97 |

| 10 | 100 | 54* | 100 |

Table 5.6. Number of particles that pass for different points on the Beta detector for E=40 keV. Note: The scanning intervals Dq = 2 deg. For points marked by *, Df = 4 deg, for others Df = 2 deg.

| 2 | 4 | 6 | 8 | 10 | |

| 2 | 131 | 137 | 131 | ||

| 4 | 258* | 292* | 150 | 292* | 258* |

| 6 | 142 | 155 | 164 | 155 | 142 |

| 8 | 145 | 160 | 164 | 160 | 145 |

| 10 | 163 | 165 | 163 |

Table 5.7. Number of particles that pass for different points on the Beta detector for E=80 keV. Note: The scanning intervals Dq = 2 deg. For points marked by *, Df = 2 deg, for others Df = 4 deg.

| 2 | 4 | 6 | 8 | 10 | |

| 2 | 140 | 149 | 140 | ||

| 4 | 136 | 153 | 168 | 153 | 136 |

| 6 | 141 | 166 | 172 | 166 | 141 |

| 8 | 156 | 171 | 176 | 171 | 156 |

| 10 | 173 | 177 | 173 |

Table 5.8. Number of particles that pass for different points on the Beta detector for E=160 keV. Note: The scanning intervals Dq = 2 deg. and Df = 4 deg.

| 2 | 4 | 6 | 8 | 10 | |

| 2 | 18 | 28 | 18 | ||

| 4 | 11 | 48 | 95 | 48 | 11 |

| 6 | 72 | 153 | 204 | 153 | 72 |

| 8 | 198 | 310 | 360 | 310 | 198 |

| 10 | 532 | 566 | 532 |

Table 5.9. Number of particles that pass for different points on the Beta detector for E=320 keV. Note: The scanning intervals Dq,Df = 1 deg.

| 2 | 4 | 6 | 8 | 10 | |

| 2 | 0 | 0 | 0 | ||

| 4 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 6 | 0 | 7 | 29 | 7 | 0 |

| 8 | 16 | 66 | 97 | 66 | 16 |

| 10 | 158 | 188 | 158 |

Table 5.10. Number of particles that pass for different points on the Beta detector for E=480 keV. Note: The scanning intervals Dq,Df = 1 deg.

Additional Figures:

Appendix A

Return to thesis table of contents.

Return to Voyager LECP Data Analysis Handbook Table of

Contents.

Return to Fundamental Technologies Home Page.

Last modified 12/9/02, Tizby Hunt-Ward

tizby@ftecs.com